St Ann's Well

Thomas Moore's 'Robin Hood's Well'

Paul Nix Collection

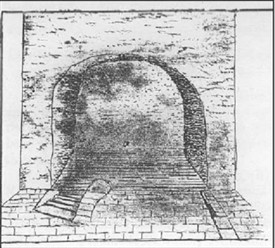

The Holy Well Immersion Bath from a 17th Century Sketch

Paul Nix Collection

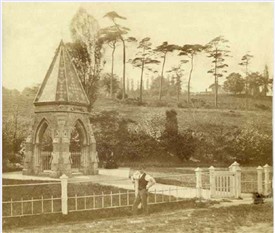

St Ann's Well c 1860

Paul Nix Collection

of Nottingham

By Joseph Earp

IT is hard to imagine now that the area covered by the St Ann's district of Nottingham was once a part of Sherwood Forest

With a few scattered dwellings, it remained covered in rough pasture and woodland until the mid-1800s.

The most important building was the house occupied by the Woodward, an officer of the Mayor appointed to manage this part of the forest.

On 'high days' and holidays, the people of Nottingham flocked in their thousands to this spot and had done so for generations.

'Thither do the Towns-men resort by an ancient custom beyond memory'.

It was not just the civic dignitaries and the common folk of

Nottingham who visited the Woodward's house. James I and

his court, including Lord Gilbert, Earl of Shrewsbury, stopped to

refresh themselves on returning from a hunting trip in the Forest.

They did so by drinking the barrels of the Woodward dry.

What attracted the good folk of the town in such numbers to such

a remote place?

It was not the Woodward's ale! The answer is the ancient 'Holy

Well' known officially as 'St. Ann's Well' – called by the people 'Robin Hood's Well'.

The Well is described in 1797 as “being under an arched stone roof, of rude workmanship”.

It was noted as being the second coldest in the country; in

fact the water being so cold that it would kill a toad. Bathing in the water was believed to cure rheumatic pains and all manner of

illnesses. We must not feel sorry for the Woodward who received a

visit from the King.

It seems that successive Woodwards exploited the fame of the Well and the house became a money making 'victualing house' – a café or pub.

An 18th century description says that it was surrounded by '… fair

summer houses, bowers or arbours covered by plashing and interweaving of oak-boughs for shade'. These were equipped with

large oak tables and earth banks for seating.

Here the public could dine on food from the kitchen or provide their own food to be cooked on the premises. All this was doubtlessly accompanied by copious amounts of ale purchased from the owner.

Two large rooms were provided for the dinners in inclement weather. Visits to the well were popular through out the year, with the summer months attracting the most visitors. However, particular attention was made at Christmas, Easter and Whitsuntide.

At a very early date a little museum – probably Nottingham's

first — dedicated to Robin Hood, had been set up. This contained items said to belong to the outlaw. These included his cap, a metal helmet, and his bow. An unusualitem was a small ivory tusk said to be Robin's tooth.

Central to the exhibition was a large wicker chair known as Robin

Hood's Chair. Young men were charged for the privilege of sitting in the chair and 'saluting' their lady friends and thus being recognised as a member of 'The Brotherhood of the Chair'.

The museum and its contents lasted well into the 18th century. However, the chair had received so much attention that it had fallen to pieces and only a small panel was displayed at this time.

An obscure medieval reference, seldom quoted, speaks of a darker practice about the Well:

‘The bodies of unfortunate criminals who were hung on Gallows Hill, a spot on Mansfield Road by St Andrew's church, were taken to St Ann's and hung in chains from trees about the Well’.

The term Well rather than Spring was used to imply that the 'spring head' had been covered or artificially channelled in the remote past.

With use by grazing animals such as deer, a natural clearing in the

surrounding woodland developed around the spring.

Such water sources attracted the attention of the earliest settlers. Water is a life-giving necessity and as safe, reliable supply such as a spring would have been considered as a gift from the gods.

We do not know how many centuries it was before this forest spring was covered and modified. Something different or special about the water, perhaps it was the intense

cold, quickly led to the belief that the spring had healing properties.

Some form of management of the site and artificial trough or basin to collect run-off is likely to have been in use long before the first Anglo Saxons arrived in Nottingham.

The earliest written reference to the Well gives the name as Brodwell, — possibly derived from the Saxon Brod, a coming together or to shoot or spout. This name was still in use as late as 1301. An alternative name occurring in written references is Owswell. It has been suggested that the element Ows is a localised Saxon word for the goddess Eostre.

However, it seems more likely that it is derived from the Saxon 'Ostarmanoth' — Easter Month, April, — perhaps denoting the time when the spring flowed at its strongest. By the time of these early references the well was already coincided as a Christian holy and healing spring and was under the care of a hermit who lived close by in a stone cell or hermitage. For a small charge the sick could take a full emersion bath in the healing waters. As the site was in a Royal Forest, the hermit of the well was paid a small fee watch-over the King's deer.

In 1216 an event took place that was to set the Well on its course in history. In this year elders of the town met with King Henry III to ask for a repeal of certain 'Forest Laws' to the benefit of the starving poor. Deer in the forest were culled twice a year and it was decided that the product of the spring cull was to be used for the benefit of the town.

The cull in the area around the Well was arranged to take place at the time of the Festival of Easter. It was made compulsory for all the 'town people' to attend at the well for a great feast followed by the distribution of meat.

Thus began the annual pilgrimage to the Well on Easter Monday. Starting with a service at St Mary's Church, a procession of all the folk of Nottingham led by the Mayor, Aldermen and Clergy walked the mile from the town gates to the Well. Here, the sick and lame 'took the cure'. From the time of the First Crusade until 1312 the site was maintained by the Brotherhood of Lazarus, under the aegis of the Knights Templars, from its headquarters in Burton Lazars near Melton Mowbray Leicestershire.

For a small donation to the Knights of St John of Jerusalem, the sick of Nottingham, under the watchful eye of the hermit, continued to partake of the curative bath. In 1314 the Pope ordered the disbandment of the Templars and seizure of their assets. However, in England, under Edward II, the Templars fared better and it was some four years later that the King began obeying the Pope's edict. The Well continued as a place of healing under the care of the Knights of St John who began to adopt Templar sites and practices from around 1320.

However, increasingly the site came under the influence of the

monks of Lenton Priory, who finally ?seized the great spring of the town'. Much to the annoyance of the local population, the Priory dedicated the Well to St. Ann. In 1409 a chapel of the same dedication was built next to the well, thus sealing the Priory's authority over the site.

From the time of its construction to its demolition after the Civil War, Nottingham Castle was a favourite of Royalty.

It is likely then that many of the Monarchs staying at the Castle or hunting in the Forest of Sherwood paid a visit to the holy healing well at St Ann's. At the very least, such was the importance of the well to the town of Nottingham they would have been familiar with the site.

It is not the Well's association with any member of royalty that made the site popular to the common people. If the stories of Robin Hood are to be believed, it was the 'trysting place' – meeting place – of the Outlaw. In the 'Geste of Robin Hood', the site is described as being 'one mile under the lynde' (one mile from the town under the forest) and ?not more than a heap of stones, fit only for a hermit or friar'.

This description, along with other elements of the story, fits the Well site. Certainly the people of Nottingham were convinced of a connection between the well and the outlaw and began to refer to it as 'Robin Hood's Well'. This title probably occurred long before any printed ballads began to circulate in the reign of Henry VII.

When the Priory at Lenton seized the Well, it was along with Buxton and Malvern — both also dedicated to St Ann — rated as being one of the three 'great healing wells' of England. It is likely that the seizure was motivated out of acquiring a lucrative source of revenue rather than a religious site. Whatever the motivation, the monk's control of the site lasted until the Priory's dissolution in 1536. From this time on St Ann's Well, as it was now called, was administrated by the Mayor and Corporation of Nottingham. Slowly the site became increasingly secular and the chapel began to fall into ruin.

Between 1543 and 1534 the records of the Corporation show money paid for repairs to 'Sainte An' Chappel'. By 1577 records show that the chapel had become ruinous and to have been partly absorbed into the Woodward's House.

Although the annual procession to St Ann's had become more of a civic event, it ceased with the outbreak of the Civil War in 1642. Because of this increased secularisation of the site, St Ann's survived the Civil War and Commonwealth. With the Restoration the well once again became popular and by the 18th century.

The Enclosure Act of 1773 saw development of the area. By the early 1800s, the old Woodward's, which had become a public house, become a rowdy out-of-town drinking den.

In 1825 matters had become so serious that the pub's licence was revoked and for 30 years it became a tea-room and then a private house. In 1857 the Corporation Engineer, Mr Tarbottom, realised that future development of the area threatened the site and constructed a large 'gothic' style monument over the Well. However, things now become a little confused and there is some dispute as to the Well's precise location.

In 1887 all buildings in the area were demolished to make way for the long anticipated Nottingham Suburban Railway and it was believed that the monument and Well were covered by one of the supports for the Wells Road Viaduct.

The railway and viaduct were demolished in 1957 and new properties built on the land. In 1987 with the demolition of the Gardeners' public house, the site of the well was believed to have been discovered in the pub's car park. This site was privately excavated by Mr David Greenwood (in 1987) and the results subsequently published in 2007 in the publication ’Robin of St Ann’s Well Road’.

Sources:

Briscoe, P., 1881. Old Nottinghamshire. London: Hamilton, Adams & Co.

Greenwood, D., 2007. Robin of St Ann’s Well Road. Nottingham: David Greenwood.

Morrell, R., 1990. Nottinghamshire Holy Well and Springs. Nottingham: APRA Press.

Morrell, R., 1994. The great spring of the township, in, At the Edge. No 21.