Edmund Cartwright & the Invention of the Power Loom

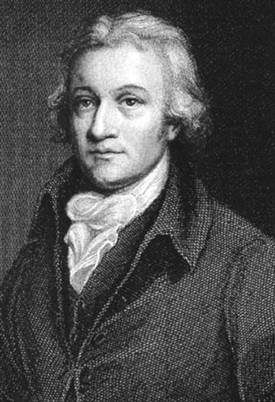

ABOVE: Edmund Cartwright (1743 - 1823) inventor of the power loom and a native of Marnham near Newark. From a commemorative engraving printed in 1889.

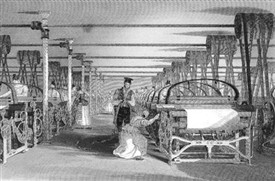

ABOVE: This fine engraving of power looms in operation in the 19th Century was published in 1835. The machines owe their originto the work of Edmund Cartwright of Marnham 50 years earlier.

From the little village of Marnham in Nottinghamshire came the inventor of a machine that would revolutionise the cotton spinning industry across the globe

A milestone in the Industrial Revolution

Sir Richard Arkwright at his mills - first in Nottingham and then at Cromford in Derbyshire - had already mechanised the production of cotton thread but it was Edmund Cartwright of Marnham who invented the machine by which the thread could be turned into cloth.

Of all the great inventors and entrepreneurs who forged the basis of Britain's Industrial Revolution, Edmund Cartwright was undoubtedly one of the least likely.

By profession he was a practising cleric, while inclination drew him towards the realms of literature and romantic poetry.

He was born at Marnham some way to the north of Newark on April 24, 1743. He was the fourth son of William Cartwright who had married his cousin, Anne, a sister of George Cartwright of nearby Ossington Hall.

Successful Sons

William and Anne had five sons, three of whom had remarkable careers. George (1739 - 1819), the second son, made a career in the army before becoming a noted fur trapper in Canada.He became widely known as 'Labrador' Cartwright. For more information on George 'Labrador' Cartwright, Click HERE

John (1740 - 1824), the third son, pursued a successful naval career before retiring to become a major in the Notts Militia.

But it was Edmund, the fourth son,through his invention of the power loom, who became the most famous of all.

Early Influences

Edmund Cartwright received his early education at Wakefield Grammar School before proceeding to University College, Oxford, when only 14 years of age.

He studied for the church and rose to become a Fellow of Magdalen College. No indication of his flair for invention had yet revealed itself, and as a young man his tastes appear to have been mainly literary.

In 1772 he published (anonymously) Armine and Elvira, a legendary poem which earned the praise of Sir Walter Scott and went through seven editions in its first year.

Also in 1772, at the age of 29, he married Alice, youngest daughter of Richard Whitaker of Doncaster, by whom he was later to inherit property in that town.

The couple began their married life at Marnham although soon moved to Brampton near Chesterfield where Cartwright served as curate.

At Brampton he concerned himself not only with the spiritual well-being of his parishioners, but also their bodily health, dosing them liberally with yeast which he considered a wonderful cure for 'putrid fever'.

A Life-Changing meeting at Matlock

In 1779 Cartwright was presented with the rectory of Goadby Marwood in Leicestershire where, it is said, he would probably have passed his time quietly pursuing his parish duties had it not been for a chance meeting during a holiday visit to Matlock in Derbyshire.

In a letter written some years later to a researcher for the first edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, Cartwright described the events of his holiday thus: "Happening to be at Matlock in the summer of 1784, I fell in company with some gentlemen of Manchester, when our conversation turned on Arkwright's spinning machine."

(Sir) Richard Arkwright had patented his Waterframe for spinning cotton thread in 1769 and later set up a cotton spinning factory at Cromford, a little way to the south of Matlock.

Cartwright continues: "One of the Manchester men observed that as soon as Arkwright's patent expired so many mills would be erected, and so much cotton spun, that hands could never be found to weave it.

"To this observation I replied that Arkwright must set his wits to work then to invent a weaving mill.

"This brought on a conversation on the subject, in which the Manchester gentlemen unanimously agreed that the thing was impracticable; and, in defence of their opinion, they adduced arguments which I certainly was incompetent to answer or even to comprehend, being totally ignorant of the subject having never at any time, seen a person weave."

Genesis of the Power Loom

Once back in Leicestershire, however, Cartwright found that the idea of devising a weaving machine had lodged itself firmly in his mind.

"It struck me," he wrote, "that as in plain weaving, according to the conception I then had of the business, that as there could only be three movements which were to follow each other in succession, there would be little difficulty in reproducing and repeating them.

"Full of these ideas I immediately employed a carpenter and smith to carry them into effect.... To my great delight, a piece of cloth, such as it was, was the produce ..."

Sadly, this first machine of Cartwright's was not at all successful, and was actually slower in its operation than a manual hand loom.

Nevertheless, it worked and proved that producing cotton cloth by mechanical means was a possibility. All Cartwright had to do now was to improve and refine the process.

It took a whole series of improvements and new patents before, finally, in 1788, his machine had reached a point where the three component processes of weaving - shedding, picking and beat-up - could be performed with sufficient speed and efficiency.

Threatening Letters & Machine Breaking

Cartwright moved to Doncaster and built a mill fitted out with his own looms, powered by a water wheel.

By later standards his mill was of modest proportions and it was certainly not perceived as posing any great threat to the livelihood of existing hand loom operators.

When, however, in 1791, he contracted with a Manchester firm who were building a factory containing 400 Cartwright looms, alarm bells began to ring.

The company began to receive threatening letters and after only 24 looms had been installed the factory was mysteriously burned to the ground.

Organised, widespread outbreaks of machine-breaking under the Luddites were still a number of years away, but the mill owners of Manchester took note: bulk orders for Cartwright's looms failed to materialise.

Another invention: a wool-combing machine

A similar reception was also being meted out to another of Cartwright's textile inventions, a wool combing machine.

This, if anything, may be considered an even more original invention than his power loom, although it too suffered opposition from existing wool workers.

As with the power loom, Cartwright's wool combing machine brought considerable efficiency savings and even in the early stages of its development could do the work of 20 hand combers.

By employing a single set of machines it was calculated that a manufacturer could save more than £1,000 per annum.

Predictably, the country's wool combers (a fraternity said to comprise about 50,000 people) were greatly alarmed by these claims and, fearing for their jobs, petitioned parliament to restrict or even prevent its use.

So formidable seemed their opposition that Cartwright, in a counter-petition, expressed his readiness to limit the number of machines to be released in any one year.

The House of Commons appointed a committee to inquire into the matter, and while little came of the wool combers agitation, Cartwright's machine was not widely taken up by wool manufacturers.

Lack of take-up brings near financial ruin

With both his wool combing machine and power loom failing to take off Cartwright found himself close to financial ruin.

He had invested a great deal of his personal wealth in developing the machines, and other members of the family had become involved in servicing the debts.

The family property was sold and in 1793, still very much out of pocket and more than a little disillusioned, Edmund Cartwright turned his back on the textile industry for good. He moved to a small house in London and began to exercise his inventive mind in other directions.

Bricks and Steam Engines

In 1795 he patented a new form of interlocking brick for house construction which as well as being immensely strong was also effectively fire-proof.

The bricks were widely feted as an excellent innovation, but since they proved far too expensive to produce, the scheme was never a commercial viability.

Two years later Cartwright patented a design for an improved steam engine in which alcohol vapour instead of steam was used to power the mechanism.

This was followed in 1823 by one powered by gun powder. Perhaps fortunately this last was never built.

A Farmer in Later Years

In later years Edmund Cartwright removed to a small farm in Kent where he tended his crops and experimented with several new agricultural improvements.

In 1800 the 9th Duke of Bedford gave him the management of an experimental farm at Woburn, where he remained until 1807.

At Woburn he promoted many of his own agricultural improvements which were subsequently recognised both by the Society of Arts and the board of agriculture.

He also continued his religious activities, acting as domestic chaplain to the duke. In 1804 Cartwright's patents on the power loom expired and with improvements made by other hands, Cartwright finally saw his invention become a source of considerable profit to many Lancashire manufacturers.

In August 1807 some 50 prominent Manchester industrialists signed a memorial to the Prime Minister (the Duke of Portland) asking the government to recognise the services Cartwright had rendered to the country by his invention.

Parliament voted him the sum of £10,000 -about a third of what Cartwright calculated his inventions had cost him. Edmund Cartwright died peacefully in 1823.

Although his early attempts to introduce his power loom and wool combing machine had met with hostility, he lived to see his inventions become an integral part of Britain's textile industry - an industry which it was said in the 19th Century, helped to clothe the world.