Spotlight on the River Trent

Trespasser

Nottingham Hidden History Team

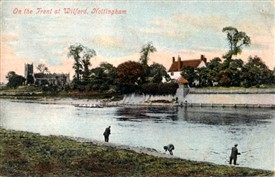

On the Trent at Wilford

The Paul Nix Collection

By Joseph Earp

AT 185 miles (294K), the River Trent is one of England's major rivers. For around half of its length, from its source on the slopes of Biddulph Moor in Staffordshire, the Trent flows in a roughly easterly direction.

Around Radcliffe-on-Trent it begins to take a more northerly direction and from Newark-on- Trent is flowing almost due north. This part of the river forms a natural boundary between the counties of Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire. The Trent ends its journey at Trent Falls, where it joins the River Ouse to become the Humber, which finally empties into the North Sea near Grimsby. The Trent is a tidal river and in ancient times, using this flow, was navigable beyond Nottingham. Later human and natural constraints on the river, including the building of Trent Bridge, limited navigation and reduced the tidal flow.

In 867 AD the Danish Vikings came up the Trent to Nottingham and Repton in their long ships. A little known fact is that the Trent, like the River Seven, exhibits a 'tidal bore' known as the Trent Aegir. When conditions are right the Aegir produces a 5ft (1.5m) wave which travels inland as far as Gainsborough. Without modern constraints, the Aegir's effect would have been felt as far as Nottingham. The River Trent, like most rivers and other natural features, derives its name from the earliest recorded language in Britain.

It is believed that the name is formed from two Celtic words – 'tros' (over) and 'hynt' (way) producing 'troshynt' (over-way). Because of the river's tendency to flood and alter its course, this has been interpreted as meaning 'strong flooding' or more directly 'the trespasser'.

Another possible meaning is 'a river that is easily forded'. The name 'Trisantona Fu (Trisantona River) for the Trent first appears in 'The Annals', the work of the Roman historian Tacitus. Researchers at the University of Wales suggest the name is derived from the Romano-British, (again Celtic) — 'Trisantano' – trisent (o)-on-a – (through-path) — which has been given the enigmatic interpretation of 'great feminine thoroughfare'. If this is correct, does it suggest that the river was regarded as a manifestation of a Celtic goddess?

Until comparatively recently, with the acceptance of the concept of the Midlands, the geographical location of the Trent was accepted as the boundary between northern and southern England. The course of the Trent and Humber separated the tribal territories of the Coritani, to the south, and the Brigantes, to the north.

The Romans under the Emperor Claudius invaded Britain in 43 AD. For political and other reasons, the Roman army did not cross the Trent into Brigante territory until 71 AD. In medieval times, the Royal Forest was subject to a separate 'Justice in Eyre' on different sides of the river and the jurisdiction of the Council of the North started at the Trent.

As indicated by one of the interpretations of the name Trent – 'a river that is easily forded' – the idea of a north/south boundary was not regarded as a physical barrier. Along the course of the river there are a surprising number of places with the Celtic rid (rhyd) — a ford, element in their name — indicating the site of an ancient ford (example, Ridware).

The Anglo Saxon element 'ford' in place names like Wilford, where in 1900 a Roman ford was discovered, demonstrates that these fords were in use for many generations. These fording places were not just a place where a track crossed a river.

AT Wilford, the way across the water was paved and black oak piles on either side marked its root. This was probably typical of such sites. That these ancient fords were later replaced by a bridge is demonstrated by places like East and West Bridgford. This does not mean that there were no bridges in earlier times.

There is evidence to show that there may have been a Roman stonebridge at Barton-Island near Attenborough. In 1985, the remains of a wooden bridge of distinctly Viking workmanship — dating from the early 11th century — were discovered in gravel workings around Castle Donnington.

There are many legends about the Trent. An omen of a coming death in the Clifton family was said to be the sight of a Royal Sturgeon, swimming up the Trent and turning around in circles in the waters bellow the hall. Another legend is similar to that of the River Dart in Devon, where an old rhyme says: 'River Dart, River Dart. Every year thou claims a heart'.

The Trent, from Trent Bridge to Clifton, is said to be dangerous and must claim four lives a year to make it safe. Could it be that gruesome finds in the river near Clifton offer an explanation for this old belief? It is the chapel, known as St Mary De Roche, which makes the Lenton caves so remarkable. It is believed that this chapel was created amongst existing caves by Carmelite Friars sometime in the reign of Edward I.

Along with the chapel, the friars built for themselves, or converted existing caves, a comfortable residence. There is evidence to suggest that the chapel may have been a'shrine' — a repository for a holy relic — like the one at Repton. Pilgrims would descend to the level of the shrine and walk around it to view the relic, leaving through a different passage. What relic may have been contained in the shrine, we will never know.

By the 13th Century the chapel had passed into the hands of Lenton Priory and the friars were replaced by monks. St Mary De Roche became an important 'satellite' chapel or hermitage to the priory. That religious importance was soon overshadowed by the priory's need for income and, in 1447, the chapel was given to the king in exchange for yet more land holdings, including some in Sherwood Forest. Part of the agreement was that the monks continued to say prayers at the chapel for the '…good estate of the King and his family'. The chapel was abandoned by the priory shortly before the Dissolution.

During periods of persecution, Nottingham's Catholics used the chapel for clandestine mass and it is this association that has led to the name Papish or Popish Holes for the site. The site may also have become a private residence. In the Civil War, the site suffered much damage by Parliamentary soldiers from the castle due to its association with the Catholic faith.

The antiquarian William Stukeley visited the chapel sometime between 1694 and 1711 and published his account along with the firstever known illustration of the site in 1724. Stukeley, with a passion for such things, declared the site to be Druidical remains. From then on, the site continued to generate and excite the curiosity and speculation of antiquarians and historians, as it still does today.