Remote Sensing in Archaeology

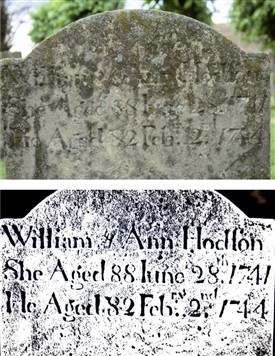

Gravestone marker enhanced by remote sensing

Dr. C. Brooke (copyright)

How scientific methods can inform heritage on buildings and edifices

By ROGER PEACOCK

17th January 2017

Archæology Studied by Means of Remote Sensing

Dr. Chris Brooke, an honorary Associate Professor of Nottingham University, delivered this unusual address to the Society in its first meeting of the New Year. Dr. Brooke is also a researcher in this field at Durham University. Beginning the theme of remote sensing as a study for a PhD, he has expanded his understanding to include several techniques of his own.

Remote sensing owes more to the disciplines of Mathematics and Physics than it does to History, but is a useful tool in heritage groundwork, revealing much that is hidden below the immediate surface of building fabrics. It can serve a similar purpose territorially and geologically.

The process makes use of the electromagnetic spectrum to decipher features hidden by time or human defilement. Such features tend to be fundamentally indestructible and can be brought to light by penetrating rays played on the subject; rays ranging between radar and ultraviolet. Only in cases of excessive erosion or partial demolition, as may be found with some grave markers, do the processes flaw. Success has been evident in older churches, where coatings such as whitewash, applied in the name of renovation, have concealed artwork that ought to have been preserved for posterity. Satellite imaging, together with aerial photography, can also say much about the material structure or matter of the physical world.

Dr. Brooke went on to list the advantages of remote sensing to the architectural historian. The processes, he told his audience, can:-

- aid examination of complex multiphase fabric, ie that subject to repair or reconstitution across the centuries, such as the walls of Newark Castle;

- reveal covered-up features of sculpture or art, including graffiti;

- identify pigments and so reconstruct ?lost' wall-paintings;

- investigate stained glass;

- decipher inscriptions rendered illegible, by time, to the naked eye;

- light saturation by laser sharpens lines of physical unevenness, such as those resulting from layering.

Multi-spectral rays are able to identify tiny differences in composition. They may enhance contours using what is termed laser contour profiling. The rays might be swept through 360 degrees as part of a thorough examination, or they may be applied from below, where weathering or human intervention has been less destructive. Other techniques include reflectography, or fluorescence, the latter being a familiar method in forensics. Mathematics then takes its place to achieve image processing. The new representation thus ekes out lost features in a two-dimensional form. Polynomial texture mapping can expand the effect into 3-D.

In conclusion, the speaker illustrated some of the revelations that his remote sensual imaging had brought to light in specific locations. A number of his examples were local sites, but others involved travel to more distant areas of the country. Averham Church, for example, had much to show of Anglo-Saxon stonework, whilst older Lincolnshire churches told of previous doorways, roof lines lost by lowering, gallery supports rendered redundant, and several other constructional changes. Laxton Church had lost texts that had been painted over. Southwell Minster has experienced floor irregularities. Upton Church owns a painting in the north chapel which has now been uncovered. Gonalston Church has stained-glass that was restored in the nineteenth century, but of which thirteenth century composition has been determined by infra-red photography. Nor is it just churches that have become subject to detailed exposure. In The Saracen’s Head inn, Southwell, a painting in the King Charles room, thought to be late seventeenth century, now suggests two phases of artwork.

Much of the strategy of remote sensing in archæology is, as stated earlier, thanks to processes innovated by Dr. Brooke himself; he specializes in this mode of research. He admitted that his work necessitated familiarity with a huge variety of computer software, upon which the processing of imagery depends. It is, he said, a developmental field. Who knows, then, what may be concealed by the edifice at the end of the reader’s own street?[1]

© Roger Peacock for NALHS: January, 2017

Edited by Dr. C. Brooke

Illustration: © Dr. C. Brooke

.

[1] For further reading and information, see Ground-Based Remote Sensing of Buildings and Archaeological Sites: Ten Years Research to Operation. Archaeological Prospection, 1(2), pp105-119: Dr. C. J. Brooke (1994)