RENSHAW, Ernest (of Mansfield)

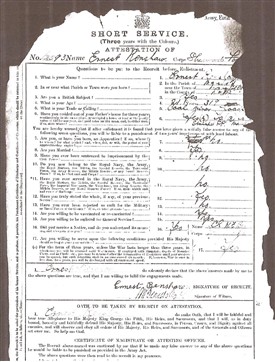

Ernest Renshaw's Attestation

Mansfield, August 17th 1914

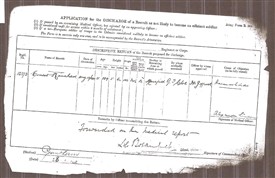

An embarrassing condition

Grantham, 28-10-1914

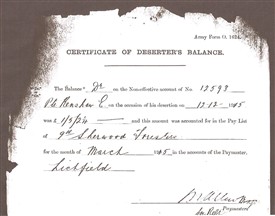

Certificate of Deserter's Balance

£1/5/2 1/4 Drawn

9th Btn, Sherwood Foresters

By Ralph Lloyd-Jones

Ernest was born in Mansfield in 1890, sixth child of labourer Samuel Renshaw and his wife Mary. The birth would have taken place at home, 13 Nursery Street. By the turn of the 19th/20th Centuries, when he was ten, they had moved to number 2 Radford’s Yard (off Nursery Street), and only one of his siblings, 13-year old Rebecca, remained there with him and his parents. He must have left school by 1903 and probably started working in the pit very soon afterwards. On 27th August 1910 he married Sarah Ann, daughter of another miner, Thomas Musgrave. In the recently-viewable 1911 Census we find Ernest and ‘Sarahann’ [sic, in his laborious handwriting] living at 39 Clumber Street. By now he was a face worker, describing himself as ‘Collier Hewer’.

On August 4th 1914 Britain declared war on Germany. The Mansfield and Ashfield Chronicle of that week mentions ‘The European War’ on page 2 inside, though a recent successful flower show provided the main story on the front page - ! This illustrates the fact that most people did not, at first, realise it would be a total war involving the whole population, imagining that the regular army, the British Expeditionary Force, would make sufficient national contribution. This attitude changed very quickly, so that within the next fortnight’s issues of the local paper great enthusiasm is expressed for the conflict and for those volunteering to boost the size of the army, as requested by Minister of War General Kitchener. Doubtless carried away by that enthusiasm, Ernest Renshaw joined up impressively early on August 17th, enlisting into the 9th Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters. We can only guess whether Sarah Ann was very proud of - or very annoyed with - her patriotic husband. They did not have any children.

From his Attestation Form we learn that Ernest Renshaw was 5 foot 6 ½ inches [1m 69cms] tall with fair hair, blue eyes and tattoos on both forearms and weighed only 120 lbs [8 stone 8 lbs]. That seems remarkably slight for a face worker, confirming the appalling diet and unhealthiness of the population in general which was revealed by enlistment in the Great War.

Private Renshaw, by now aware of the realities of army life, first absconded a month and a day after he had joined up, on September 18th. He disappeared from camp in Grantham, Lincs until 22nd, perhaps managing to cross Nottinghamshire from east to west and getting back home to Mansfield? Wherever he went, they caught him, and Lieutenant Colonel Sadler awarded 168 hours Field Punishment No. 2: ‘This meant a note in the paybook, pay forfeit, sleeping under guard and the performance of such fatigues and pack drills as could be crammed into the day. All the while the offender would be on a diet of water and biscuit. Worse, he would not be allowed to smoke...’ (Winter, p.43) Sure enough, he lost five days’ pay, as recorded on his Conduct Sheet.

Although he had passed his initial, quick Medical in Mansfield ‘fit for the Army’, on October 28th the doctor at the depot in Grantham, making a more detailed examination, discovered haemorroids and filled in Army Form B. 204, an Application for the Discharge of a Recruit as not likely to become an efficient soldier. Whether this process took a long time, or whether the application was simply rejected, Renshaw remained in the camp at Grantham.

Unpleasant though Field Punishment may seem, it was not effective in dissuading our man from making another attempt on November 23rd. This time he was AWOL for eight days, but was caught by two Sergeants at 1 a.m. on December 2nd. That suggests a late night call to his home in Mansfield; where else could he flee to? He was taken back to Grantham and given the same sentence, 168 hours Field Punishment No. 2, now forfeiting 10 days’ pay. On December 5th, when the 168 hours (= 7 days) cannot yet have been completed, he made a third bid for freedom ‘Breaking out of camp while undergoing Field Run’, evading capture for five days. That resulted in another ten days FP No.2.

Ernest Renshaw finally deserted army for good a week later. There exists a Certificate of Deserter’s Balance debiting him with the wonderfully precise sum of £1 five shillings, tuppence, one farthing ‘on the occasion of his desertion on 12-12-191[4]’. This was recorded by the Paymaster in Lichfield [who accidentally wrote '1915', though he meant the previous year]. By now the army was much too busy to pursue every individual deserter – there would be infinitely more men avoiding military service once conscription started a year later. He was simply 'Struck off the Strength' on January 16th 1915. It was obvious that this particular person was never going to be a soldier, he probably got a civilian job with reserved status, perhaps back in a pit? Needless to say, he does not appear anywhere in the British Army Medals Index from the First World War.

It is interesting that when he joined up, Renshaw gave his father, mother and brother (who was serving in the Royal Navy on the cruiser H.M.S. Liverpool) as next of kin, 'Wife - Sarah Ann', now at a different address in Mansfield, was only added as an afterthought.

He died in Sheffield in 1955 aged 65 [BMD Index].

References: All documents mentioned can be seen online on Ancestry.com (free at NCC Libraries).

Winter, Denis : Death’s Men, soldiers of the Great War (Allen Lane, 1978) – highly recommended as a revealing description of the soldiers’ experiences, 1914-18.